Fairfield University’s Bellarmine is perched on a hill in Bridgeport, housed within a century-old church now equipped with state-of-the-art classrooms. The campus’ synergy of historic and modern elements reflects the undercurrent of the Jesuit ideals within the program. The preservation of scholarly tradition, paired thoughtfully with a flair for innovation and a commitment to social justice. Fairfield Bellarmine’s mission is “to provide a Jesuit and Catholic education that is accessible and affordable and empowers underrepresented students to realize their God-given potential and serve their communities.”

The first class is comprised of 44 students, primarily low-income and first-generation, who were uplifted by a team of dedicated educators. The following interviews provide a glimpse into the academic offerings of Fairfield Bellarmine through the lens of five faculty members.

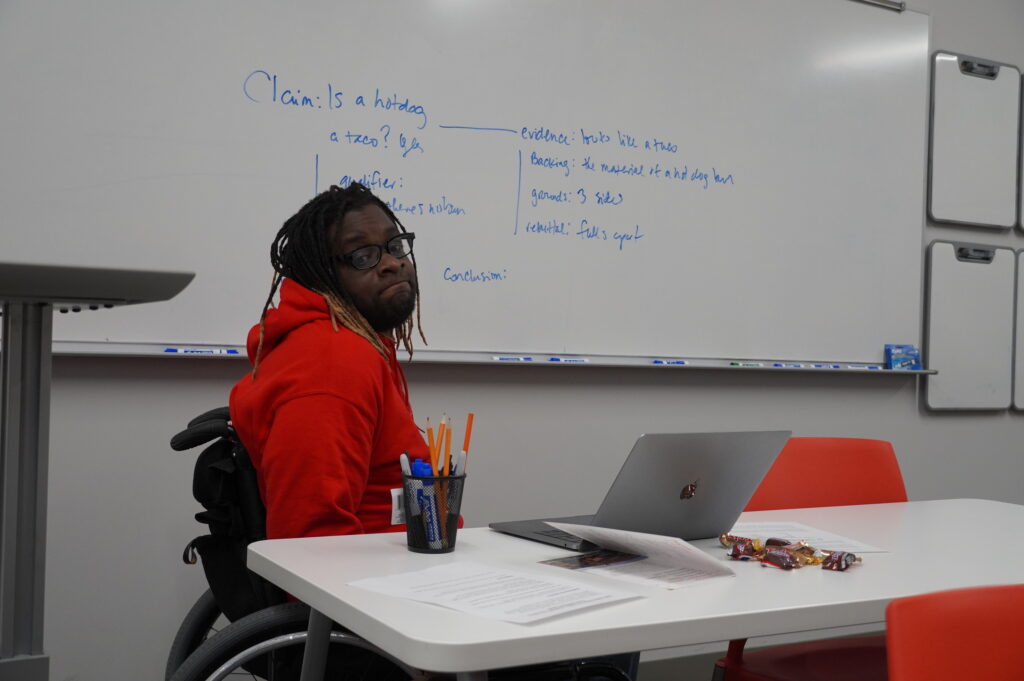

D’Arcee Neal, Ph. D.: Professor of the Practice, English

D’Arcee Neal, Ph.D. conducted his first Bellarmine interview in Hong Kong at 4 a.m., black coffee with a splash of skepticism coursing through his veins.

“To be perfectly honest, if I had done a little bit more due diligence and checked into it, I may not have applied,” Neal confessed.

Neal’s hesitation was rooted in the “squeamish” feeling he associates with Catholicism, the religious tradition that is the lifeblood of Fairfield University.

“As a Black person who is also queer and a wheelchair user, I have had religion thrown in my face my entire life,” Neal explained. “I’ve been told I don’t have enough faith to get up and walk, which is just nonsense.”

However, Neal relied on the endorsement of his mentor Kim Gunter. His willingness to trust Gunter, an Associate Professor of English at Fairfield, proved to be fruitful. Neal was employed on April Fool’s Day, which seemed like “a really weird joke” that made him “really, really excited.”

Today, Neal feels privileged to have been gifted a rare opportunity to serve Bellarmine’s unique population and uses his platform to undermine false narratives about the program’s underlying purpose.

“I look at the Bellarmine program as reparations,” he proclaimed. “The education system is stacked against people of color in the United States. There are so many obstacles that people put in place, many of which people have zero control over by the time their children get ready to go to college.”

However, Neal does not classify the initiative as “segregation” or “charity.”

“It would be segregation if we put the program on campus and never spoke to them again,” he clarified. “It’s all about how you frame it and your frame of mind. We’re in the United States and we created this opportunity. It’s not charity. It is an opportunity.”

As he addressed misconceptions about Bellarmine, Neal considered his ideas about the program’s origins.

“I’ll just be honest. I feel like initially, it started as a white savior initiative,” he said. “But, it has turned into an actual thing. We don’t have white folks running stuff. We’re the ones making decisions.”

José Luis Fernández, Ph. D.: Professor of the Practice, Philosophy

José Luis Fernández, Ph. D. is well-versed in the work of Immanuel Kant, a passion only matched by his love of opera.

Within the Department of Philosophy, Fernández can be found singing impromptu arias and drawing upon the ideologies of his favorite Enlightenment thinker. He hopes that Kantian principles will enable his students to recognize “the intrinsic worth and value of all human beings.”

“My interactions with students at Bellarmine are no different than my interactions with students here at North Benson,” he explained. “It involves the same level of admiration and respect. It involves a deep concern for the entire person, in which we value each other to the highest limits.”

Through his instruction, Fernández strives to dismantle the notion of distance often felt between students and their professors. He is committed to creating a space where his students will not only recognize the fullness of their academic potential, but the fullness of their humanity.

“If there is one big takeaway from philosophy, it is nothing other than a reflective appreciation of who we are in relation to others,” he shared. “If I can come into possession of my most fundamental qualities as a human being, I can then look at another person and see the very same thing reflected back to me.”

Fernández underscored the value of collaboration, noting the collaborative spirit he fosters within the classroom environment. A key facet of this collaboration takes place in the mini-tutorials he conducts to prepare students for essay writing. As his pupils present their papers, Fernández feels humbled by the trust instilled in him.

“I can sense their vulnerability and try to remove the feeling of being judged,” he noted. “The paper is just an academic exercise that is meant to improve a skill and not a judgment on the human being.”

At a lecture hosted by Father O’Brien, S.J., a handful of Bellarmine students reflected on the most memorable course that had taken thus far. Fernández recalled a particularly touching moment when a former student acknowledged the lasting impact of his teaching.

“The student shared that philosophy had provided a level of questioning that was performed within a safe space,” Fernández recounted. “We can push the boundaries of the ideas that we have internalized in society. In that sense, philosophy was a very disruptive process. But, it was one that he found very rewarding.”

To Fernández, disruption is required for progress. He hopes that, as the Bellarmine program evolves, the Fairfield community will embrace the unparalleled initiative.

“There is always going to be pushback to innovation,” Fernández declared. “But, pushback and resistance will eventually give way to acceptance and praise.”

Ryan Harper, Ph. D.: Professor of the Practice, Religious Studies

Ryan Harper, Ph. D. has a storied history. His upbringing was shaped by two opposing settings, as he grew up in rural Missouri before entering the Ivy League.

Harper earned his Ph.D. at Princeton University. But, he was raised by a father without a high school diploma and a mother who returned to college when he was in high school.

“My experience splits the difference between North Benson and Bellarmine,” Harper determined. “I know a little bit about the world of some of these Bellarmine students, but still got to grow up in a world of some white entitlement. So, I’m in the middle of the two spaces.”

At Fairfield, Harper continues to coexist amongst varied populations as he teaches religion courses at both campuses. He referred to this experience as “a great experiment between the two populations.”

“My students at the North Benson campus, by and large, are well-groomed to be students. They get their stuff in and they show up on time,” he noted. “A lot of my students at Bellarmine are still learning those skills. However, the Bellarmine students are so engaged in discussion and when I go to North Benson, it’s like crickets sometimes. ”

Harper believes that the students of both campuses could learn from each other, which emphasizes the necessity to bridge the gap between the groups. The challenge lies in the longstanding divide between these communities, which has existed far before the establishment of the new program.

Yet, Harper wishes to fall back on the Jesuit values to find common ground.

“It seems like the Jesuits always go into spaces as people who need to learn from the space and the people there,” he said. “They go to the space, not to convert, not to be these hero missionaries, but to learn from their fellow citizens and to see what they can teach you.”

Harper characterized teaching as his vocation, a calling that highlights the sacred nature of his profession. He also finds inspiration through poetic expression. When asked to devise a poem about the Bellarmine program, he shared a thoughtful response.

“I would structure it in such a way that it would be both formalistic, but also free verse,” he imagined. “It would go in and out of form because my experience of this place is that it has both structure and improvisation.”

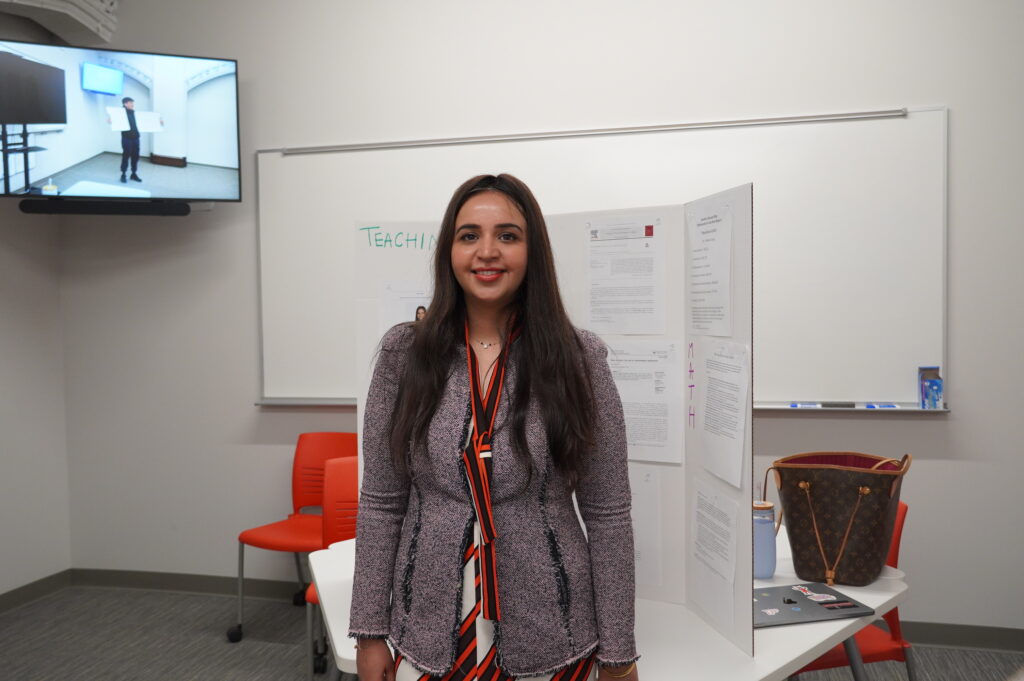

Neha Hooda, Ph. D.: Professor of the Practice, Mathematics

Neha Hooda, Ph.D. is in awe of her students’ perseverance, as their daily responsibilities do not end once they step off the Bellarmine campus.

“They are managing so much and are putting on so many hats,” Hooda exclaimed. “They are doing their job and are financially responsible for their families. We have found ways to work with the students at their own pace. Yet, we never dilute the quality of their education.”

Hooda enhances the educational experience through a student-centric approach that stems beyond the curricular requirements. Her goal is to weave a thread between faculty and students, especially as the Bellarmine population may face challenges that are different from a “typical student.”

“A lot of our students are first-generation students who don’t have mentors or older siblings at home who they can ask, ‘What is an office hour?’ or ‘What is the registrar?’” she explained. “All they have is their peers and the faculty and staff. For this program to be successful, the first essential step is the sense of community.”

The unity felt within Bellarmine’s close-knit cohorts allows individuals’ inhibitions to fade. Students fearlessly voice their questions in their pursuit of knowledge, both in the classroom and in the newly founded STEM Club.

Hooda attributes this comfortability and capacity to “co-construct knowledge” to the fact that she is not only viewed as a professor, but as a friend.

Outside of academia, Hooda finds joy in the culinary arts. She has earned a reputation for her skillful fusion of cuisines, intertwining her rich Indian heritage with global flavors. In the kitchen and at Fairfield, Hooda understands the immense value of diversity.

“Bellarmine has opened pathways,” she concluded. “It is not just for the students and their families, but Fairfield University will benefit from including students who will bring their own stories and experiences.”

Tina Santiago: Professor of the Practice, Biology

“As a kid, I had always wanted to go to Fairfield,” Tina Santiago revealed. “But, we couldn’t afford it.”

Santiago, a Bridgeport native, possesses an intimate understanding of her students. She graduated from Harding High School, situated less than a mile away from the Bellarmine campus. Santiago’s entrance into higher education was not seamless, allowing her to learn lessons of life that could never be taught with a textbook.

“I had to go to work and take one course at a time to get to where I am,” she noted. “I wouldn’t trade what I went through, because it shaped who I am today.”

Fairfield Bellarmine serves low-income and first-generation students in Bridgeport and surrounding Connecticut communities. Santiago had to confront the same barriers faced by this population, which makes her work endlessly gratifying.

“Because I had to struggle so much to get to where I am, it means that much more that other students don’t have to struggle that way,” Santiago shared with a warm smile.

In a single word, Santiago would describe her students as “courageous.” The construction of the Bellarmine campus, which is housed in the former St. Ambrose Parish, was not unveiled until September 15. Therefore, the inaugural class decided to enroll while their new school was still in a fragmented state covered in sawdust.

“It was still a church,” Santiago remarked. “It was so brave that they said, ‘Yes, I’ll go to this university,’ when there was nothing to see.”

An element of the unknown still prevails, as Santiago acknowledged the necessity to continue spreading awareness about the program.

“I wish there was a bigger event where the Bellarmine initiative was explained to everyone at North Benson and the public in general,” she said. “Communication is important and it has to come from the top down.”

Santiago feels compelled to advocate for her students. She is empowered by her belief that education must be accessible to all, regardless of their geographical location or socioeconomic status.

“Education is for everyone, whether you are rich or poor,” Santiago asserted. “Just because we are over here in Bridgeport, it does not mean that we are not members of Fairfield University.”

Photos By: Kathleen Morris

Leave a Reply