A little over a year ago, John J. DeGioia, President of Georgetown University, announced the recommendations of the University’s Working Group on Slavery, Memory and Reconciliation. This group was formed in response to student protests over Georgetown’s slave-owning past and racial discrimination in American educational institutions. They were tasked with addressing the legacy of Jesuit slave owning and slave trading at Georgetown. The working group made a number of recommendations — the most noteworthy ones being the promise of formal and regular dialogue with the descendants of those 272 Jesuit-owned slaves and the rest of the university community, the renaming of Mulledy Hall and Remembrance Hall to Isaac Hall and Anne Marie Becraft Hall and the granting of legacy status and tuition assistance to the descendants of the 272. These initiatives garnered Georgetown a fair amount of good publicity.

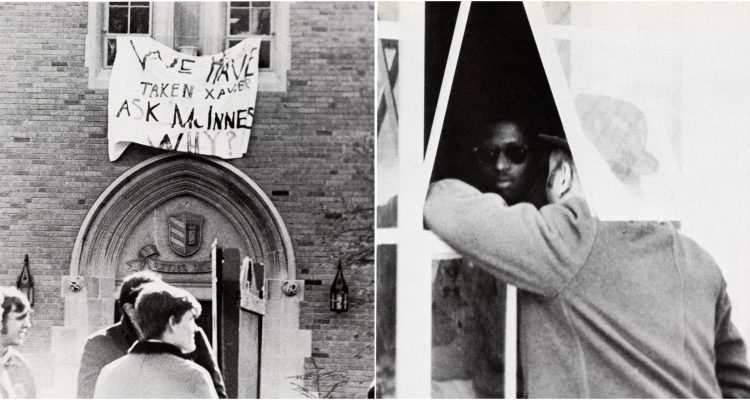

Protests from student-activists of color were the driving force behind Georgetown’s reckoning with its slaveholding past. Without their prodding, Georgetown’s reckoning might have gone the way of Holy Cross’ — which ended in the unsatisfying compromise now known as Brooks-Mulledy Hall. Echoing Yale student protests over Calhoun Hall, named after the infamous slaver John C. Calhoun, these student-activists demanded that, in light of the Jesuit involvement in the slave trade, Mulledy Hall be renamed Building 272. These protests didn’t arise spontaneously; they were organized by student activists of color, included the entire campus community, and inspired by similar demonstrations of people of color across the country and the globe.

However, before the student protests occurred, Georgetown wasn’t particularly enthusiastic about coming to terms with its institutional history with slavery. As reported by the Washington Post, the announcement of the working groups’ recommendations was actually one of the first public acknowledgments of the Jesuit order’s role in the Atlantic slave trade. In fact, a report from NPR details the story of Richard Cellini — a curious class of 1984 Georgetown alumni — who discovered that a representative from the working group originally claimed that all of the formerly Jesuit-owned slaves died shortly after they were sold and transported to Louisiana. A statement that proved to be false after a cursory Google search by Cellini revealed that most of the descendants were alive and well in Maringouin, La. Yet once the Jesuits and Georgetown became aware of the existence of these descendents, they made little attempt to contact and consult them about the plans for memorializing their ancestors.

This inconsistency between the University’s public pronouncements on race and their actual record on race isn’t a phenomenon that’s unique to Georgetown. It’s an issue that affects Jesuit educational institutions across the country. Despite frequent pronouncements about the importance of social justice to Jesuit educational institutions, Jesuit universities aren’t run much differently than typical secular American universities. Most aren’t any more affordable than the typical secular American university—only Boston College, Holy Cross and Georgetown qualify as need-blind, 100 percent need-met universities. Their racial demographics can be just as unforgiving to people of color — in most Jesuit Universities white students make up around 70 percent of the student body and they use the same tactics — subcontracting, benefit rollbacks and gendered and racialized departments — to keep on-campus workers marginalized, underpaid and underappreciated. Jesuit Universities are similarly reluctant to look beyond the usual suspect with respect to recruitment and admissions.

In fact, the tendency to ignore non-traditional students is even reflected in recommendations of the working group. For instance, some descendants justifiably claim that granting descendants legacy admission status and tuition assistance mainly benefits college-aged descendants who have the qualifications and resources to apply to and gain admittance into Georgetown. Since the vast majority of descendants are neither college-aged nor likely to be admitted to Georgetown, most will have little opportunity to act on the main redistributive segment of Georgetown’s memorialization project. They were left out of the process and it shows in the recommendations. A clearly mapped out and well-funded commitment to incorporate older and under qualified descendants into these legacy and tuition assistance programs could have put Georgetown at forefront of the movement for racial justice in American educational institutions. These initiatives should have extended to investing in the community and educational infrastructure of Maringouin.

If the election of Donald Trump and the protests and counter protests that developed in its wake tell us anything about the state of our nations, it’s that racial conflict isn’t going away anytime soon. Every racial battle may not be as deadly or as well covered as Charlottesville, yet Jesuit universities owe it to their students, campus workers and communities to speak out against and be active in combatting all forms of racial injustice. Jesuit universities can’t hide behind platitudes about free speech and neutrality if they want folks to take their pronouncements about social justice seriously. In cases like Charlottesville, silence serves as an endorsement of the status quo. If we all don’t start speaking out against racism and racial injustice, then public safety will suffer, public trust will erode and our democracy won’t survive. Jesuit educational institutions need to take the cue from student activists and become the driving force behind our nation’s reckoning with its slaveholding past.

A recently released independent report on the unrest in Charlottesville revealed that the Charlottesville Police Department lacked the equipment, instructions and resolve needed to stop the violence that was unfolding in front of them. If we can’t rely on our local police forces to prevent and investigate racialized violence, then who should we turn to when seeking protection from racist mobs? And if we can’t rely on our universities to speak out against and sincerely combat these racial injustices, then who should we turn to when the next racial tragedy inevitably occurs? I feel that the obvious answer to both questions is to turn to each other. Folks may need to start taking responsibility for each other’s safety because clearly the white supremacist state cannot be relied on for protection. And members of every university community may have to turn to each other and start organizing and agitating until American universities stop ignoring their responsibility to keep their students, campuses and communities safe from racism and free from racial injustice.

Leave a Reply