There’s a show I watch on CBS during the summer, partly because there’s nothing else on except mindless game shows and late night talk shows, but also because it’s a fairly good program. “Salvation” is all about the months leading up to the arrival of a meteor meant to crash into and destroy Earth and the politicians and scientists working to prevent this from happening. As cheesy as the premise is, the execution isn’t all that bad, and the cast of lesser-known actors, including a favorite of mine, Santiago Cabrera, brings a fairly good level of talent to the story. However, as much as I’ve treated “Salvation” as an almost literal salvation from the boredom of summer’s lackluster TV line-up, I had several moments while watching it this summer where my frustration couldn’t be contained. During nearly every episode I’d have reason to shake my head, gesture angrily at the TV and yell out loud (often just to myself), “No no no no no, are you kidding me? What is happening, this is so beyond stupid!”

Now, to be fair, it doesn’t take much to get me riled up if I’m sitting alone watching something, and “Salvation”’s second season had quite a few annoying plot developments from the very first episode. However, what caused me to shout in such utter disgust was the way the majority of the romantic storylines in this show were handled going into the second season. Relationships built up with considerable care over the course of the first season were carelessly swiped away in pursuit of a single charged, impulsive kiss or one-night stand meant solely for shock value. I guess what disappointed me the most was that I saw it all coming from a mile away, because it’s as though nearly every mainstream TV show or movie must include an unnecessary heterosexual romance, in whatever shape or form that takes.

The unnecessary heterosexual romance can be exemplified by a single scene we’ve all viewed countless times before. It’s basically a filmed version of, “He was a boy, she was a girl, can I make it any more obvious?”: a man and woman have little to no effort put into building their romantic relationship, but there comes a moment where, in the middle of their conversation, they fall silent, make prolonged eye contact and then, of course, they kiss. It’s the “of course” that drives this entire construct, that because we live in a heteronormative society, heterosexual romance is expected whether it makes sense and adds to the wider narrative of a story or not. Straight couples are perceived as what is more natural and adds to the misconception that men and women can’t “just be friends”; it’s expected that romance plays a part in every interaction and is almost inevitable. A huge franchise like the Marvel Cinematic Universe is so guilty of this that most of their romantic pairings look downright lazy; pairing up Captain America (Chris Evans) with Bucky Barnes (Sebastian Stan), his lifelong friend who he’d die for, makes leagues more sense than making him kiss Sharon Carter (Emily VanCamp), a character so forgettable and brief that I had to Google her name before writing this. And don’t even get me started on the utter, maddening ridiculousness of Black Widow (Scarlett Johansson) and the Hulk (Mark Ruffalo), a pairing so random that it still infuriates me to this day.

A main reason I find this trend so abhorrent is that it can do serious damage to individual characters, namely women. A popular trope within this idea surrounds a woman having multiple male characters competing for her affections and placing her in a “who will she choose?” scenario. Then, after she has made her choice, she will often turn to her other option at the slightest conflict with the one she chose, making her seem flighty, more interested in the attention she receives than in building something stronger and unable to make solid and healthy decisions about her love life. That’s not how good writing is done either; it’s not sustainable and treats the story as something temporary that needs to fit in every possible partner combination for the ultimate shock value.

This representation of a flighty, attention-seeking woman is also found in another common trope, wherein a woman leaves a relationship with a man because she doesn’t find it healthy for her, but eventually returns to that original relationship even after being in a happy, healthy new arrangement because the original guy was there first and “gets her more.” It’s the show trying to sell the audience on love at first sight, and the two characters having to struggle and grow before finally getting to be together, but more often than not this acts as yet another predictable plot point that just makes me want to scream at my TV even more. I’ve seen it happen in countless shows, from another favorite though less popular show “The Bold Type” all the way to a massive hit like “How to Get Away with Murder” or “The Fosters”.

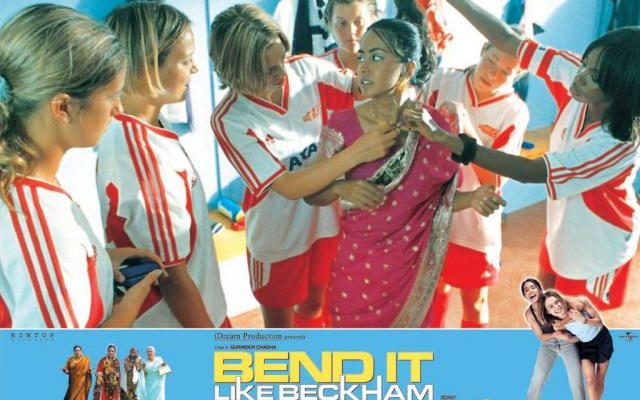

Something else to consider: where, then, does that leave LGBTQ+ representation in mainstream television and film? Due to the relative newness of this representation in our media and the expectation of straight relationships, a frustrating double standard has emerged for gay characters that are given screentime. A classic example is the wonderful 2002 movie “Bend It Like Beckham”, a film I genuinely love even though it plays into this trope in the most heavy-handed way. The two female protagonists, Jess and Jules, get as close to being girlfriends as they can be without being explicitly named as such, something that’s played as a recurring joke throughout the film. Though they obviously both genuinely love and care for one another, and share a strong passion for soccer, a relationship between them is foregone in favor of pairing up Jess with their male coach, making him a romantic partner for her simply by his existing and being male. Not only that, but her pairing with their coach serves as a source of division between the two girls, as Jules is supposedly also attracted to him and sees Jess’ interest as a betrayal. In a movie with such abundant examples of queer subtext, this plot point constructed to create tension between the girls is ludicrous, driving them apart rather than uniting them in what is a boring, predictable path for the story to go down.

With all the calls for diversity in the characters and stories represented in our media, it’s also time to call for diversification in just how we tell those stories. Not only are unnecessary heterosexual romances in mainstream media utterly useless and disheartening, they destroy female character’s sense of self as independent people with arcs not focused on men and erase queer identities all together. We need new stories with new perspectives, but we also need already existing stories to break from well-worn ground that shows in the past have trod, take the road less travelled and make smarter decisions when it comes to their romances.

Leave a Reply