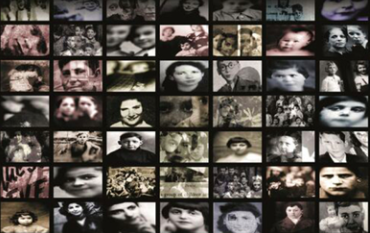

It’s their eyes you see first. They stare into you, at you. Brimming with dreams and hopes for the future, of wishes to be nurses, teachers, parents, to grow into whoever they were meant to be in the future. We don’t know them personally. They could be anyone: a sister, brother, cousin, friend, a face seen once in a crowded room. Yet, we do know them. They are the 11,000 French children sent to their death for their religion. They are the faces of Robert Hirsh’s “Ghosts: French Holocaust Children,” a new exhibit being displayed at the Walsh Gallery in the Regina A. Quick Center for the Arts until March 2.

There are no labels on any of the pieces. You walk around and look at the collages, a mix of large scale photos and mixed media objects and wish to see the names of the children, but there are none to be had. You instead see their eyes. The collages mixing portraiture images with otherwise blurry backgrounds: unfocused, unimportant. There are other, non-portraiture photos included in the collages that play an integral part in the story being told: birth certificates, the Star of David and newspaper clippings give us insight into a world we were not a part of. But still no labels. This, the blank spaces between each print, forces us not to look and read, but to feel.

As you enter the gallery there are three fabricated train cars just to the right. Tiny faces peek out just between the gaps of the small barbed wired windows. Stuck in a prison cell, serving a death sentence for a choice they never made, for a life they were born into. Their small space is only delicately lit, just a few of the children’s faces glow in the light. An unknown, and seemingly unintended depiction of the handful of (300) children that survived the Nazi’s purge. Without the labels, without knowing their names, we have no way of knowing the fate of the children displayed.

In the discussion before the exhibit opened, the present and imminent importance of the showing and reteaching of the Holocaust was discussed. Due to the resurgence of anti-Semitism in our present time, we no longer look at these faces and see the past. We look into the eyes of these children and see the horrors they saw: the death and destruction of lives and homes, the killings of millions with a six-pointed star placed on their chest, and are remind of what we see when we turn on the news. The terrorist attacks and hate crimes placed on members of the Jewish faith. Crimes performed by people who still see their Jewish neighbors as being different, as not belonging, just as the Nazi’s believed that being Jewish made the French citizens less French.

When studying history, it becomes challenging for many to compare the past to the present. As we wish more than anything for the future to be placed on this pedestal of tomorrow, the possibility and hope for all the good things to come for the next generation, we slowly realize, as we see past ideas mimicked and events mirrored in our modern era, the importance of listening to the stories of the past. By looking in the eyes of the innocent and being unable to see what distinguishes them from sisters, brothers, cousins and friends. By taking the time to sit and listen to the children’s stories in the only way they’re able to tell us, we become a witness. A quote said by Holocaust survivor, Elie Wiesel, was read aloud during the opening of the gallery, “Whoever listens to a witness, becomes a witness.”

Leave a Reply