Empress Catherine the Great of Russia is known for her unlikely military victories, her focus on raising the opinion of Russia in the eyes of world powers and for the vast collection of priceless masterpieces which she purchased over the course of her reign. These pieces ranged from works the empress commissioned to placate stilted lovers then purchased back once they died, to works created by some of the greats, including Rembrandt and Michelangelo. While the general public knows a lot about the individual pieces included in this collection, the same cannot be said about the time and circumstances surrounding the momentous occasion when all of these pieces resided together in St. Petersburg. An event that turned Russia into “a world wonder,” as the woman who sought to rectify this knowledge gap, Susan Jaques, announced at her lecture in Bellarmine Hall’s Diffley Board Room.

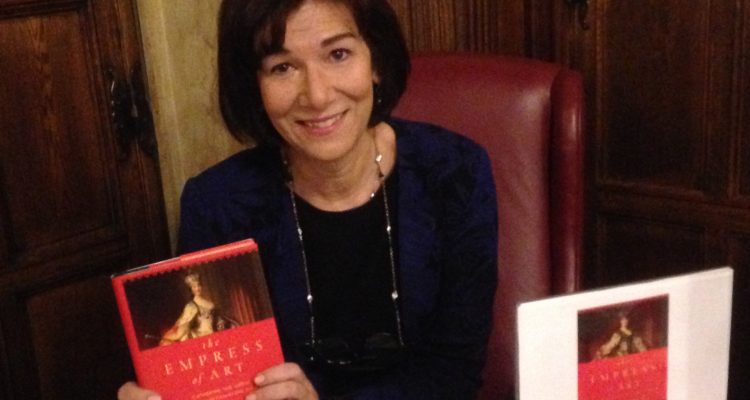

To promote her book, “The Empress of Art: Catherine the Great and the Transformation of Russia,” Susan Jaques, a member of the Historians of the 18th Century Art and Architecture group, spoke to a group of Fairfield town residents about the collection “in honor of the 100th anniversary of the Russian Revolution.” While the event was lacking in attendance from the student population, it was none the less a fascinating and educational experience, made all the better by Jaques’ readily apparent expertise and her infectious passion for the subject. This knowledge has been long gathered. Jaques graduated from Stanford University with a major in history and went on to both earn an MBA from the University of California and be a docent at the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles. In a summary of this accumulation of knowledge, which is encased in her book, Jaques took the time to detail both why art was important to Catherine the Great and how the empress collected the vast collection that resided in St. Petersburg, Russia during her lecture.

Catherine the Great had a passion for art and architecture that developed over the course of her 34-year reign as tsarina. In fact, her ascension to the throne resulted in her first commissioned piece, her coronation crown, created by Jérémie Pauzié. The five pound creation, which cost an eighth of the state budget, would be the first of hundreds of pieces commissioned by the tsarina. She utilized several of these commissioned portraits and art for propaganda. Before she was crowned, Catherine’s husband, Peter III, tried to have Catherine extruded from the royal line for having an extra-marital affair. In response, Catherine lead a revolt against her husband that resulted in his strangulation at the hands of a man who was then promoted to the position of Commander of the Russian Navy. This same man, Aleksey Grigoryevich Orlov, would inspire one of Catherine’s favorite propaganda paintings, a commemoration of the Russian victory named “The Destruction of the Turkish Fleet in the Bay of Chesme.” To ensure this painting was accurate, the tsarina had Jacob Philipp Hackert, the painter, procure another military ship, light it on fire and watch it burn.

Catherine the Great had highly specific tastes in art. She disagreed with any and all senseless nudity, seeing it as not being a proper interest for an enlightened ruler — a persona she attempted to portray to convince the world powers of the time that Russia was not a “backwater” country. The exception to this rule was if the nude figures were part of a mythological portrait, such as in the Jean-Antoine Houdon statue of Greek mythology’s Diana. Catherine was also very interested in neo-classical art and came to acquire Michelangelo’s unfinished masterpiece, the powerful sculpture of the “Crouching Boy,” a sculpture with no mythological context that features a nude male.

Catherine the Great never again left Russia once she took the throne, which made her very skilled at re-gifting artwork that she disliked after purchasing it sight unseen, but also prevented her from viewing Michelangelo’s murals in the Sistine Chapel. This troubled her as she had become fascinated with his work through her acquired sculpture and from reading of it in her books. Determined to see the works in one form or another, she dedicated an area in the Hermitage Museum where the works could be recreated in one of her most magnificent commissions. The art spans the entire expanse of the hallway just as it does the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel.

While some work has been lost over the years and some pieces have been separated from the collection, the majority of this artwork can be viewed unscathed in the Russian Hermitage museum in St. Petersburg. Susan Jaques’ lecture only gave a taste of the rich history of Russia’s art, filled with entertaining tales, torrid love affairs and shopping sprees that cleared the Russian royal coffers, but also enabled Catherine to reach her goal of turning Russia into a cultural hub to aid in its rise to world power status.

Leave a Reply