My desk is placed in the back corner of my bedroom, away from the long reach of the sunbeams that flash through my front window, its white lacquered surface collecting dust from disuse. As an expensive and exceptionally large piece of furniture purchased by my parents long ago, it’s a disappointment to us all as it is only used as a resting place for lost books and papers rather than for its intended purpose.

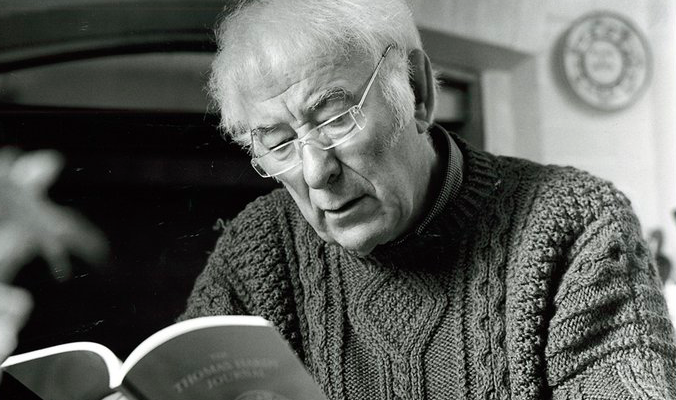

Seamus Heaney’s desk, on the other hand, was put to good use. His desk is less ornate than mine, as it’s quite simply a piece of wood laying across two metal filing cabinets. I learned this bit of information on Oct. 4 during a lecture titled “Seamus Heaney: The Dublin Exhibit” and presented by Geraldine Higgins, Emory University associate professor of English, specializing in 20th Century Irish Literature. She said that even as the Nobel Peace Prize-winning poet started to gain a bit of fame and recognition, he kept the same desk. He was worried changing anything about his process would negatively affect his work.

Though the presentation was about her work curating the exhibit on Heaney at the National Library of Ireland, Higgins began her presentation with a photo of Heaney’s desk. The photo was from a 2007 series of articles done by U.K. newspaper The Guardian, highlighting different writers’ workspaces and showing us a connection between text and context, as this does seem to be an obsession of ours as a society.

As a society, we seem to have a desperate need to connect further with the authors we love, or maybe to deeper understand the work they created that we love just as much. It’s the same reasoning behind why we visit their homes – Herman Melville’s Arrowhead, Agatha Christie’s Greenway or Mark Twain’s house right in Hartford, Conn. We’re obsessed with finding the place they penned our favorite words. We want to see what they saw, heard, felt as the words we hold so dear bled from their pen tips.

However, when asked about the photo of his desk, in that 2007 Guardian Article, “Writers’ Rooms: Seamus Heaney,” Heaney started to list the things that aren’t present in the picture. Stating that, “In the down-slope of the ceiling on the other side there’s a second skylight, much wider and longer and lower than the one in the picture, and through it I have a high clear view of Dublin Bay and Howth Head and the Dublin port shipping coming and going – or not, depending on the weather.” He never states it directly, but Heaney wants to show us that there are things unseen and deeper that can’t be seen by just peering at his desk. That seeing his desk or visiting any of the homes of our favorite authors might connect us closer to their work, but there needs to be more.

In the Seamus Heaney exhibit, there’s a conscious effort to further connect viewers with the work. When you see Heaney’s poem, “The Rain Stick,” on the wall in the Dublin Exhibit, you look just toward the left and Higgins placed a physical rainstick for the viewer to interact with when reading the piece. When you read his first line, “Upend the rain stick and what happens next…” you turn the rain stick, listening to the soft beads pittering down. Or, if you view his more political pieces written during the Troubles in Northern Ireland, these poems are placed near newspaper headlines of events that would place you mentally where Heaney was when he wrote them. All in an effort to place us in his shoes, the same reasoning behind showing us his desk. It’s not just about the words that we want to connect with, it’s about the person who wrote those words.

This eventually becomes a tiresome event, as I feel like the more steps I take to put myself in the author’s shoes, the more I feel disconnected to the piece itself. Though I love, just as much as anyone, the idea of getting closer to my favorite authors. There’s a magic to be had about analyzing the piece itself and translating its meaning to match your own life.

Leave a Reply